The Fauntleroy Legacy

One of the first things I establish about the main character of The Convergent Eigenspace is that Cedric is not his birth name. In fact, the short prologue, told from the perspective of his friend Diana, does not reveal a name for Cedric at all. For Diana, she recognizes that his birth name no longer refers to the individual she has come to love, and yet, his chosen name represents his future: a future that necessarily lacks her presence. I allow Cedric himself to introduce his name when the narrative switches to his viewpoint in the following chapter. The continuing difficulty for him to adjust to life behind his new name is a theme I revisit throughout the first act. It is never an easy task to reconcile our inner and outer selves, but it is worth doing, and key to the path toward self-actualization and adulthood.

Cedric begins

At the end of the prologue, as Cedric is preparing to leave his hometown, he visits Diana to say his final goodbye. As she sits on a tree swing outside her house, he hands her two library books and asks if she could return them. As Cedric had aged into high school, he had begun to find it more and more difficult to slip into the world of whimsy found inside the pages of a good story. But as he looked for inspiration for his new identity, he found himself returning to where he had begun.

The name “Cedric” first appears in Walter Scott’s 1819 novel Ivanhoe. The name, having never before appeared in literature, is thought to be a misspelling of the name “Cerdic”, most famously referring to an Anglo-Saxon king who ruled over Wessex from 519-534 A.D., perhaps even founding this kingdom of a people known as the Gewisse. Although the native origin of the man is disputed, “Cerdic” is a name of Old English origin, and its most famous bearer instilled upon it connotations of bravery and leadership. There is little doubt Scott intended a comparison to be drawn between Cerdic and his character Cedric; the Saxon nobleman possesses a deep-seated pride in his heritage. His patriotism is somewhat of a liability, however, as he struggles to maintain a relationship with his son, the titular Wilfred of Ivanhoe, when the latter displays a sympathy for the Norman crown. For Scott, his character is not simply a king from the distant past, indeed, he inherits this throne, but is nevertheless something new. What is important to note about Cedric in Scott’s novel is that he is capable of character growth, and where he had once disowned his son, he is able to change his mind in the face of new information, becoming open to Norman ideals and allowing his son to marry the woman of his choosing.

Cedric hits it big

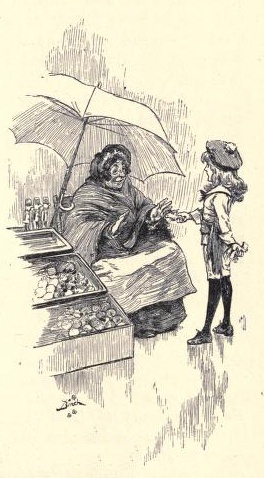

It is not until Frances Hodgson Burnett publishes Little Lord Fauntleroy in 1886 that the name becomes familiar to a wider audience. In the first of Burnett’s bestsellers, we are introduced to Cedric Errol, a seven-year-old American who finds he is the only remaining heir of the Earl of Dorincourt. The young boy travels to England to meet his grandfather and eventually wins the heart of the surly old man by virtue of his generosity and beautiful heart. This classic rags-to-riches story appealed to audiences on both sides of the pond with kindness triumphing over cruelty, wisdom worth more than wealth.

Although the modern reader might be somewhat more familiar with The Secret Garden and The Little Princess, it was Little Lord Fauntleroy that skyrocketed Burnett to fame at the end of the nineteenth century. While English by birth, she later emigrated to the United States and used her knowledge of the two countries to provide commentary on the virtues of both cultures. Despite being marketed as children’s literature, little Ceddie appealed to a wide audience and inspired a number of plays based on the novel, some of which Burnett helped bring to fruition.

Adults were taken in by the gentle strength of the young boy and his popularity spurred a viral trend in children’s fashion. The book sold over 43,000 copies in its first year, making it one of the best-selling English novels of its time. Velvet suits with lace collars, directly imitating the dress of the character, were marketed as “Fauntleroy suits” and remained popular well after the release of the book.

The long delicate curls worn by Cedric also peaked in popularity, and were often worn by people portraying him on stage, especially in the early decades of the twentieth century. While the broad appeal of the novel and its characters was not the first such trend in popular literature, it remains a key example of early marketing before the invention of the Internet, television, or radio.

Childhood and the Ideal Boy

Cedric Errol, despite being played by women in a number of stage productions, was never intended to be a weak portrayal of manhood. To the contrary, Cedric participates in activities to be expected of a young boy: he wins a footrace against his friends and demonstrates humility in the face of victory.

He displays an interest and talent in horsemanship, far from being a woman’s domain, especially in England. Despite his rudimentary grammar, he makes a habit of keeping correspondence with his friends and associates. And perhaps most importantly of all, he displays immense respect and affection for others, be they people in positions of power over him, like his mother and grandfather, or people from whom he stands nothing to gain. When he arrives at Dorincourt, Cedric stands in stark contrast to his grandfather, a rather miserly man beset with violent fits of gout that betray his inner greed and resentment. It is little Cedric, with his bright outlook and optimism, that endures as the best personification of what a young person can be, and his crowning achievement is convincing the Earl of Dorincourt to change his ways.

Changing Perceptions of Manhood

The hardships faced by the world in the wake of the Great Depression and World Wars led to a steep decline in the popularity of stories that dealt both with the nobility and ultra-rich. This period also saw a vast pivot toward a very different view of masculinity. Utilitarian styles of fashion became preferred, and a militaristic inspiration for men’s dress reflected their thoughts and aspirations. The people had gone through significant trauma, and their changing sensibilities reflected an ideal man that did rather than felt.

Rejecting one who might refuse to take up the gun, “Little Lord Fauntleroy” became an insult, a slur to damn its target as pampered, priggish, and, perhaps even more directly, feminized. The boy’s admirable qualities of generosity, idealism, and wisdom were ignored in light of the greater shame: that he was somehow in violation of the precepts of masculinity. But perhaps what we need is a little more Fauntleroy.

Comments

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!

Leave a Comment

Thank you!

Your comment has been submitted and will appear after approval.